Written by Cathy Okada

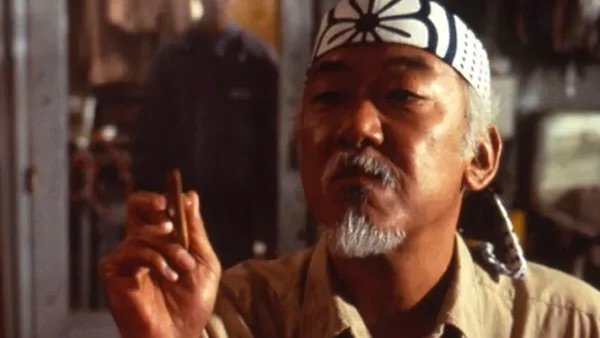

In the West (or at least in the UK) we all know what a sensei looks like; an elderly Asian man with a white beard. Mr Miyagi and Pai Mei spring to mind. And of course Ueshiba Morihei, O Sensei himself.

People are so fixed on O Sensei’s image being as the photo on most Aikido dojo’s kamiza, that recently there was an amusing debate on Facebook as to whether a picture of O Sensei was actually him, as it was a younger photo of him with a shorter beard. “It’s not Ueshiba,” one guy proclaimed with full confidence.

Perhaps this stereotypical image of a sensei is one of the reasons that the students in the dojo of a friend and senior Karateka, Yanti Amos Sensei, instead of addressing her as “Sensei” would call her “Senpai”, even when practitioners outside of the dojo in the rest of the world call her “Sensei”. This changed upon the members being directly corrected by the dojo-chō.

The Japanese word sensei (先生) is written with two kanji:

先 (sen) → “before, ahead, previous”

生 (sei) → “life, birth, living, student”

Literally, 先生 means “one who was born before” or “one who came before in life”. In Japan it is used to refer respectfully to teachers, masters, doctors, and other professionals- people who have gone ahead in experience or knowledge. In martial arts, sensei usually means “teacher”, but the nuance is closer to “one who has gone ahead on the path of learning.”

Sometimes people in the West address themselves as Sensei. For example they might sign off an email: “Kind regards, Joe Bloggs Sensei,” which is considered rather odd in Japan. It is also an honorific, like san, chan or kun– words used to address someone else. I notice more and more that sensei can be such a loaded word here that people either overdo it, underdo it, or are just straight-up awkward about it.

We recently had a long-term student suddenly and rather dramatically exit the dojo and exit the training permanently. The reason was never clear. In terms of dojo etiquette, in many ways this student was exemplary. He would bow upon entering and leaving the dojo, he was always punctual and he would always pack away the mats and often be the last one making sure they were locked up. But there was something odd; this student never called either myself or Ivan “Sensei”. Not in the dojo and not even on the tatami. I always found it kind of funny that people I have never met address me as “Sensei” on Instagram or Facebook (not that I want or expect them to), and yet a regular member- in fact the most regular member of our own dojo would not.

Maybe there was something there that he just couldn’t yield. His parting email thanked us for our “help” rather than our teaching. Maybe a part of him never accepted us as his teachers, and so perhaps in the end he never really was our student.

I know of teachers in the West who insist on being addressed as Sensei by their students at all times, in all situations (in Japan they don’t need to insist, it’s just a given). In our Women Talk Budo interview with Roo Heins Sensei, she said: “…if you see me at the grocery store, please just call me Roo.” Similarly, my own teacher always said that outside of the dojo “Ismail” is fine. Most people understandably just call him Sensei in every situation anyhow. For me, in the dojo (regardless of whether or not you are instructing in that moment) or in any other training context, I just see it as good manners.

I think that ultimately, for a lot of people, addressing the teacher/s as Sensei means having to let go. Let go of any big or small ideas about yourself, your identity, and your position in society. Surrendering to the path. Like the famous Zen kōan of Nan-in, it is part of the emptying of one’s cup. Perhaps this is why people apparently find the “S” word so uncomfortable to use at times.

Of course as these practices cross borders and travel in time, the context changes, and will naturally experience some transformation. However these traditional Eastern systems have a deep history to them. Aikido is considered a modern art but at its core it is old, built upon thousands of years of warrior culture. If we start cherry-picking which bits suit us, and which bits we won’t bother with, or that cause us some discomfort, doesn’t something get lost and watered down?

There was something Ivan said to me:

“I was just thinking how Buddhism took about 800 years to become ‘Chinese.’ Chan is the result of centuries of mixing with the local Daoism, Confucianism and many other smaller beliefs. Similarly, Kamakura Buddhism with Zen, Nichiren and Pure Land can be said to be the maturing of nearly 700 years of communication of these ideas between China, Korea and Japan mixing with Shinto, for lack of a better word.

To think that Aikido leaves Japan 60–70 years ago and the West can do whatever it likes to it is ridiculous.”

When it comes down to it, our position is clear: You can take the Art out of Japan, but you can’t take Japan out of the Art.